Blogpage with articles, essays & more

Christheguide

5/8/202450 min read

The Greatest Archaeological Discovery in Dutch History Is in New York

on Whatevr #12

"Vandaag bied ik excuses aan. Eeuwenlang hebben de Nederlandse staat en zijn vertegenwoordigers slavernij mogelijk gemaakt, gestimuleerd en ervan geprofiteerd. Het is waar dat niemand die nu leeft persoonlijk schuld draagt voor de slavernij, maar de staat draagt wel verantwoordelijkheid voor de immense pijn die aan tot slaaf gemaakten en hun nakomelingen is aangedaan." – Mark Rutte, 19 dicembre 2022

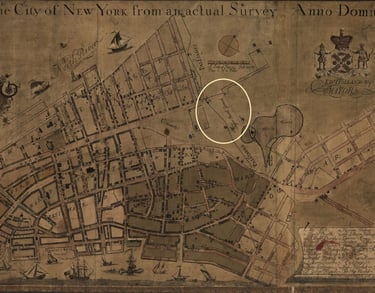

The story of one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the late 20th century begins in May 1991 in New York, at 290 Broadway, in the heart of Manhattan. Construction had just begun on a massive project: a new skyscraper, the Federal Office Building, with an estimated cost of $276 million. But the building would never be completed. During excavation for the foundations, bones began to emerge — in large quantities. Their nature soon became clear. In fact, their possible presence was already suspected: there had once been an old cemetery on that site, a cemetery for enslaved Africans, used between 1630 and 1795. Over two hundred years had passed, and most assumed it had vanished amid the transformations of the modern metropolis. Yet, about ten meters below ground, it resurfaced: the African Burial Ground.

It was an extraordinary stroke of luck. The remains were remarkably well preserved, thanks to the fact that in the late 18th century, before the cemetery was abandoned, it had been covered by some seven meters of earth and debris during a yellow fever epidemic — a protective layer not unlike the volcanic ash that preserved Pompeii. Construction halted, and archaeology took over.

What emerged was a necropolis containing the remains of over 15,000 individuals. As excavations continued, the magnitude of the discovery became clear: not only the largest African cemetery ever found in the United States, but also a crucial testimony to the origins of New York. An ancient American cemetery, a cemetery of enslaved Africans, in Manhattan, New York!

One might exaggerate and say that the great cultural capital of the Western world is literally built on a foundation of slavery and oppression. Perhaps it is an exaggeration, a provocation — but there is some truth in it. The role of slavery in the development of the New World, even in the North, is well known but often underestimated, due in part to the long-standing myth of the North as the anti-slavery champion against the slaveholding South.

The milestones are familiar: Independence on July 4, 1776; the first abolition laws starting in Vermont in 1777; then the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery on December 18, 1865. But what about before 1865? What were conditions like for enslaved people in Manhattan under Dutch rule, then under the English, and in the early years of the United States? The discovery of the African Burial Ground has opened a new chapter in this story, forcing us to reconsider and re-examine with new — tragic and invaluable — evidence the history of New Amsterdam and New York.

I should pause here. Perhaps, as a white person and half-Dutch, I have no right to tell this story. I apologize for choosing to do so, with honesty and some shame. Yet this is also the story of an extraordinary discovery, an archaeological miracle, a priceless new historical source — and today, a museum that deserves to be visited as much as MoMA or the Met. So I will go on.

To understand the importance of the African Burial Ground, we need to step back to the origins of New York, when it was still New Amsterdam. Founded in 1625 as an outpost of the Dutch West India Company, the city received its first Africans in 1626: eleven men captured from a Portuguese ship. We even know their names, which were geographical in nature: for example, Paulo Angola, Simon Congo, Ian Fort Orange. Eleven enslaved Africans among a population of 300.

The Dutch slave system differed from the English model that would follow. Though required to pay a tax to the Company, Africans enjoyed a form of semi-freedom: they could own houses, farm land, sell produce, and access the courts. This allowed the development of an active African community that contributed to building key infrastructure such as Fort Amsterdam, the defensive wall that gave its name to Wall Street, Broadway, and other features of the nascent city. In short, while still forcibly uprooted and enslaved, Africans in New Amsterdam played an active role in shaping the new colony, with duties but also limited rights. To be clear, this does not absolve the Dutch Republic of its immense responsibility for the history of slavery: the guilt is indelible, a wound to be remembered as a permanent scar.

Around 1650, this community was granted a plot of land for burials — thus was born the African Burial Ground of Manhattan.

But in 1664 everything changed. The English arrived, and New Amsterdam became New York, named for the Duke of York, James Stuart, brother of King Charles II — himself a major shareholder in the Royal African Company, a slave-trading enterprise. Under English rule, conditions for Africans deteriorated drastically. The relative freedoms of Dutch times were replaced by increasingly oppressive measures, such as the appointment of a “Whipper of the Slaves” and severe restrictions on funeral ceremonies. New York also became a central hub of the slave trade, in stark contradiction to its later image as a symbol of liberty. The cemetery was closed at the end of the 18th century and disappeared from maps — until 1991, when plans for a new skyscraper uncovered it once more, in exactly the wrong (or perhaps the right) place.

In 2003, the remains were honored in a solemn ceremony, and the area was declared a National Monument. Today, the African Burial Ground is not only an archaeological site, but also a place of memory and reflection.

This discovery marked a turning point, not only for the history of New York, but also for public archaeology. During the first stages of excavation for the Federal Office Building, techniques were rushed and disrespectful: the goal was to move quickly and continue with the skyscraper project. But this risked erasing forever a crucial part of the city’s history. The African American community quickly realized this and, through protests and heated debate, forced a change of course. The skyscraper would not be built.

The excavation was placed under the direction of Michael Blakey, a serious and highly respected African American anthropologist — a symbolic choice, restoring dignity to those who had been forgotten too long. More importantly, the work was done properly. Thanks to a careful, respectful approach, archaeologists recovered an invaluable heritage. The remains revealed not only malnutrition and abuse, but also African funerary practices and cultural traditions that had survived deportation.

Though shocking to New York’s multiethnic community, these stories are a treasure trove, reshaping the history of the city and its inhabitants. A trace of the past that inspires both shame and pride, awareness and surprise. A testimony, a reaffirmation of collective memory that — thanks to archaeology and the determination of the African American community — has become a necessary monument, a global archaeological heritage that enriches New York, and all of us.

The greatest archaeological discovery in Dutch history

on Whatevr #7 Leonardo da Vinci, a Baby Genius

While this article may not act as a guide to raising a baby genius, it will give you an idea of the early years of one of the greatest geniuses of the modern age, who, being human, was undoubtedly once a baby and then a child before assuming the appearance of the bearded old man in the iconic portrait. Our main character is none other then the legendary Leonardo da Vinci, born on the 15th of April, 1452, in the middle of the night in the small town of Vinci or, more precisely, the hamlet of Anchiano, halfway between Florence and Pisa.

We’ve chosen to feature Leonardo because the year 2019 marks the 500-year anniversary of his death on the 2nd of May, 1519, at Clos Lucé, a castle in the city of Amboise, France. On that day, as Francis I was holding his head and lamenting the loss of that great man, Leonardo whispered his last words: “I have offended God and mankind because my work did not reach the quality it should have.” It was the perfect farewell of a genius – or so the legend goes.

This year, a number of cultural institutions will be celebrating the anniversary of the death of that astounding polymath. The most eagerly anticipated event will be the mega-exhibition at the Louvre, scheduled for the autumn of 2019 and likely to be one of the greatest cultural events in recent decades.

And so, as Whatevr #7 celebrates childhood, we’ll be focusing on the mysterious early years of the man of the year. But before we begin, we have to warn you that the little we know about those years is based on scant historical records and lots of wild conjecture.

Not surprisingly for the time and place, Leonardo was born out of wedlock. From his DNA, we know that Leo was the illegitimate son of the Florentine notary Piero di Antonio da Vinci and the orphan girl Caterina di Meo Lippi, so while Leo’s father came from a wealthy family, his mother was considered a nobody. Also a notary, Leonardo’s grandfather Antonio made a record of his grandson’s baptism, including all witnesses who attended the event – and what instantly stands out is that Leo’s mother was not there. It was clear that this would not be a happy family and that the baby was not wanted – at least, not at first.

Baby Leonardo may have lived with his mother during the first years of his life, but by 1457, at the age of five, we find him staying in the house of his grandfather, Ser Antonio, in Vinci. Living in the same house was Leonardo’s grandmother Lucia, the descendant of a Majolica artist-craftsman family, and Leonardo’s young uncle Francesco, who was a member of the silk guild of Florence . Leonardo’s father, who married another woman several months after the child’s birth soon moved to Florence, where he served as a notary for the Medici family, married three more times and had thirteen children.

And what about Leo’s mother, Caterina? We know that she married a farmer and that they had four children together. Beyond that, we know next to nothing. She and Leonardo may have met years later in Milan, a few months before Caterina’s death, and we know that Leonardo paid her funeral expenses.

With so little solid information, the road was wide open for a string of speculative theories on Caterina’s origins. A perfect example is the story of a Chinese girl captured by Mongol raiders and sold as a slave: first in the Crimea, then in Constantinople and finally in Venice. Having arrived in the Italian Maritime Republic she was bought by a wealthy Florentine businessman, Ser Vanni, and brought to his house in Tuscany to help his wife with the chores. Vanni happened to be one of Piero Vinci’s clients, and it was there in the Vanni household that the sexual assault on Caterina took place and where she conceived Leonardo. The book that sets forth this theory is now a bestseller in China – no surprises there.

The story is certainly a spectacular fantasy, but it’s not completely unrealistic. In Renaissance Italy, domestic slaves were often referred to as Tartars or Orientals. According to Italian university researchers who have been reconstructing Leonardo’s fingerprints from those found on his drawings and paintings, the central whorl, a common fingerprint pattern found in the Middle East, suggests that Leonardo’s mother may have come from that area. Approximately 60 percent of the Middle Eastern population evidently have the same pattern, which leads us to ask: did Leonardo da Vinci have Turkish, Arab, Tartar or even Chinese origins?

Whether that’s true or not, it makes for a great story. But the best is yet to come. The theory goes on to suggest that the scenery behind the Mona Lisa resembles a typical Oriental landscape such as Leonardo might have seen on a Chinese fan in his mother’s possession. Furthermore, the Mona Lisa herself is apparently not the image of Francesco di Giocondo’s wife, Madama Lisa Gherardini, but a disguised portrait of Leonardo’s mother Caterina. Yes, the most famous European portrait of all time is now thought to be the likeness of ... (drum roll) ... a Chinese slave in Europe, 500 years ago – the mother of a genius. It just goes to show the power of globalization is nothing new.

But let’s go back to the small town of Vinci and the house of Leonardo’s grandfather Antonio. How did Leonardo spend his time? Later in his life, the artist would record only two childhood episodes in his codices. The most famous one reads as follows:

“It seems that it had been destined before that I should occupy myself so thoroughly with the vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory, when I was still in the cradle, a vulture came down to me, he opened my mouth with his tail and struck me a few times with his tail against my lips.”

Sigmund Freud used this quote, which is incorrectly translated into English from the Codex Atlanticus (the “vulture” is actually a kite), in his highly debated work Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood (1910). An interesting read. About sexuality. Guess you probably knew that.

The second incident occurred at a time when Leonardo was exploring the Tuscan mountains around Vinci and one day happened upon a mysterious cave. The darkness of the cave terrified young Leonardo, as did the unknown danger of what might be lurking inside. But his curiosity drove him to explore what was there in spite of his fear. Leonardo most likely wrote the story to illustrate the power of human curiosity. Then again, some pseudo-historians prefer to see the cave as, yes, a stargate or time machine that he could have used for time travel or close encounters of the third kind – no doubt the perfect explanation for Leonardo’s futuristic engineering projects.

The earliest record of Leonardo’s artistic talent is mentioned in a biography written by Giorgio Vasari a few decades after the artist’s death. In it, Vasari describes how a family friend asked Ser Piero if his talented son could embellish his new shield. Leonardo responded by painting some terrifying images of fire-breathing snakes on the round plaque. The monsters looked so real and frightening that Piero sold the shield to a Florentine art dealer and made a huge profit in the process.

Whether this story is true is unknown, but we do know that Ser Piero brought young Leonardo along to Florence to improve his artistic aptitudes. Perhaps Leonardo’s father thought that, as an illegitimate child, his son would not have the opportunity to become a notary like himself and the boy’s grandfather. Leonardo’s skills in arithmetic were also apparently inadequate. Florence, however, had a variety of successful artist studios where Leonardo could serve as an apprentice, and a career as an artist was considered a respectable position in the society of that time.

The decision was made: the young boy would become an artist. In 1466, Leonardo was documented as frequenting the workshop of the great master Andrea del Verrocchio (featured in a marvelous exhibit in Florence this year), with such immortal “schoolmates” as Botticelli, Perugino, Ghirlandaio and Lorenzo di Credi, all future great masters of the Florentine Renaissance. The situation could not have been better: Florence was one of the most advanced cultural centres in Europe at that time and Verrocchio’s “talent scout” atelier was the best place for a boy as gifted as Leonardo to grow and learn. Verrocchio was moreover not only a painter but also an architect, sculptor and goldsmith. The resulting exposure to a vast range of technical skills that included mechanics, chemistry and carpentry as well as painting, drawing and modeling enabled Leonardo to improve all his skills and gifts. As he learned how to use the different paintbrushes, colours and pencils, he developed an irresistible passion for the natural sciences and soon concluded that deduction was the only road to real knowledge: theory alone was no longer enough. Taking part in the atelier’s creations between 1466 and 1476 also helped to shape Leonardo into the man we know today, a man whose passion for observing and comprehending the laws of nature and physics was focused on improving his skill as a painter. This, then, was the learning environment of one of the greatest maestros of Italian art and culture.

The earliest work of art associated with Leonardo is The Baptism of Christ (1472), a painting attributed to Verrocchio and on display at the Uffizi. This painting was clearly the work of different hands, and as Ser Vasari documented once again, Leonardo was among them. But while Leonardo was only one of several apprentices who contributed to the work’s creation, his skill and style so surpassed the rest that Verrocchio himself – so goes the story – put down his brush, never to paint again. While that may be exaggerated, almost all art historians agree that Leonardo painted the more beautiful of the two angels as well as the backdrop to the scene. There is also no doubt that both the figures painted by Leonardo and that of John the Baptist, most likely the work of Botticelli, reveal a modern spirit unlike any prior Florentine creation. The golden generation was rising. Leonardo was now a fully fledged artist; and so, our story comes to an end.

But before we say “over and out”, let’s go back to the beginning to answer one more question: what did Leonardo look like in his younger years? What was his outward appearance before he assumed the look of a wise Greek philosopher? His biographers describe him as first, a nice-looking boy and later, a handsome man: tall and graceful, strong and valiant. According to tradition, he was the model for his master Verrocchio’s carving of the famous bronze David, now housed in the Bargello National Museum in Florence. If this is true, we can imagine the young Leonardo as a good-looking youth, slender and muscular with long, curly hair – and on his face, just a hint of an enigmatic smile.

by Christheguide

published on #7

Chris the Guide on Whatevr Fanzine #6: I paint my pictures with all the considerations

Chris the Guide on Whatevr Fanzine whatevr fanzine #6: I paint my pictures with all the considerations

“We painters have the same licence as poets and madmen.”

Venice. July, 1573. It’s a hot morning on the Venetian Lagoon as the sun casts its light upon the city, lending it an unsurpassed beauty. The Republic is experiencing a new and glorious age. Less than two years have passed since the Venetians, along with the other “crowns” of Europe, defeated the Ottomans in one of the greatest naval battles in history: the Battle of Lepanto. For a brief time, and also the last time, the Mediterranean Sea was once more known as the “Sea of Venice”. Meanwhile, Europe was back at war, with the Catholics and Protestants fighting in Flanders and at sea. War for Venice had always meant big business but also great danger. The Republic had usually been adept at maintaining enough political weight to tip the scales in its favour, but this time, things were getting out of control. The Catholic party had grown strong – too strong.

The champion of the Catholics was Philip II, King of Spain – the richest man on earth. Even in France, which had always been the traditional rival of Spain, the Catholic party was triumphing. King Charles IX and his Italian mother Catherine de’ Medici had slaughtered most of the Calvinist Protestants, the so-called Huguenots, in one night – the infamous St. Bartholomew’s Night of 24th August 1572. On that day, every bell tower in Rome rang, with Gregory XIII sitting on the Throne of Saint Peter. Now famous for the Gregorian Calendar, Pope Gregory was a great defender of papal supremacy and the Counter-Reformation. The Catholics had never been so strong, and even independent and “libertine” Venice was seeing the rapid growth of that powerful armed wing of the Church, the Inquisition.

Such was the political situation in July of 1573, when Paolo Veronese, the leading painter of the Venetian School, was called before the Court of the Inquisition. Paolo Caliari – better known as Veronese, after his place of birth – was an important man of the town. Respected and wealthy, his life was a great success – until now. To be called before the Inquisition was fraught with danger, and Veronese knew it. Venice’s Inquisition was less strict than those of other cities, but it was still the Inquisition; and an accusation of heresy, especially if proved, could destroy the artist’s career and potentially end his life. Yet on that day before the Court, Paolo Veronese – who was neither a hero nor a deliberate defender of human rights – transformed that dangerous inquiry into one of the brightest episodes in the cause of creative freedom.

The painting now hangs in a large room at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, under the title: The Feast in the House of Levi. It is perfect just as it is, uncorrected and uncensored; and the colourful collection of odd guests, of dogs, dwarfs and soldiers still remains – exactly as the artist painted them in 1573.

The casus belli was the content of one of Veronese’s paintings: the great and beautiful Last Supper, which he painted for the Dominican Monastery of Saints John and Paul. The painting remains in Venice and can still be viewed at the Gallerie dell’Accademia. It measures almost six metres long and portrays a feast, a joyful gathering of Jesus and the Apostles surrounded by jesters, dwarfs, dogs, weapons and – worst of all – drunken, heretic Germans.

This cannot be The Last Supper, argued the tribunal. Who are all these ridiculous characters? The accusation was correct and threatening: the painter had clearly not followed the guidelines. A religious painting was supposed to represent the content of the Gospels, while this rendition, even by our modern standards, looked more like a bachelor party than a religious sacrament. The situation could have taken a turn for the worse, had Veronese not managed to refute the charges with a sharp and courageous rebuttal.

The following excerpts are from a translation by the French writer and draughtsman Charles Yriarte (1832–1898):[GM1]

Q. “Did some person order you to paint Germans, buffoons, and other similar figures in this picture?”

A. “No, but I was commissioned to adorn it as I thought proper; [the canvas] is very large and can contain many figures.”

Veronese admitted that the monastery’s abbot suggested he insert the Magdalene in place of a dog to make the painting more in accordance with Holy Writ. But the painter considered it against his artistic sensibility, arguing that it would irreparably destroy the harmonious balance of the composition.

Q. “And the one who is dressed as a jester with a parrot on his wrist, why did you put him into the picture?”

A. “He is there as an ornament, as it is usual to insert such figures.”

Veronese was most likely afraid, yet though he respectfully acknowledged his mistakes with regard to the guidelines, he stubbornly defended his creative rights as an artist:

“I paint my pictures with all the considerations which are natural to my intelligence, and according as my intelligence understands them.

Veronese did nothing less than follow the leadings of his artistic eye. Is that a crime or a flaw? He painted halberdiers, drinking men and Venetian nobility because it seemed to him an accurate and appropriate portrayal of life in La Serenissima, as the Republic of Venice was known. And he was paid for it. Yet Veronese was simply doing his job, and in his view, he was doing it well. An artist creates art according to his imagination and personal taste, and for this he requires complete freedom, without the risk of censorship. This is his duty and role in society, for the job of the artist is not to preach but to entertain and inspire.

It was then that Veronese spoke the words that made this trial a legend: “Noi pittori ci pigliamo la licenza che si prendono i poeti e i matti.” Here he is citing the Latin poet Horace while adding an unmistakably modern touch: “We painters have the same licence as poets and madmen.” A wonderful, flawless defence – no further explanation required. It bears repeating: “We painters have the same licence as poets and madmen.” For in this single sentence, the sanctity of creation is set.

The Court of the Inquisition gave Veronese a lenient sentence. He had to change the title of the work to The Feast in the House of Levi, described in the Gospel of Luke as a banquet held by the tax collector Levi, who invited Jesus and the Apostles as special guests amongst a larger crowd of “publicans and sinners”. The story does not describe the guests in detail, nor does it possess the religious intensity of the Last Supper, thus giving the artist more space for creative ideas. For Veronese, the incident was a great victory. He would not be forced to make changes and could continue to paint in line with his taste and imagination. The painting now hangs in a large room at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, under the title mentioned above. It is perfect just as it is, uncorrected and uncensored; and the colourful collection of odd guests, of dogs, dwarfs and soldiers still remains – exactly as the artist painted them in 1573.

[GM1]Inserted to explain the slightly strange, old-fashioned language and also to give credit to the source.

Chris The Guide on Whatevr Fanzine #4: Curvy Rubens

Curvy Rubens by Chris The Guide

From whatevrfanzine nr.4

Whoever decided to buy Whatevr #4, will certainly want to browse through it calmly, without being noticed too much though, that’s “not done”. Whatever is certainly not a novel or an essay, you don't need to lock yourself up in your study room.

Reading it in the underground could be perfect, but the paper size is too big and the passenger next to you might get annoyed when hit by your elbow. Perhaps a table in a coffee shop, but even there, a failure, the magazine is printed on A3 size, too big, the pleasure of browsing is denied again, it’s either Whatevr or the bad “caffé macciato” you just ordered. No, no way, you need peace, but not at home, for heaven's sake, no. The armchair is for a novel, or for a nap. Besides, we are talking about the new issue, brand new, and novelties need to be read immediately to breathe the new trends instantly.

I have a better idea: since this new Whatevr has a very specific topic namely food, food and the body, and the curvy beauty, perhaps a filthy trattoria is the place to go. In this case though, I recommend just fatty food, no vegan, please. If this suggestion is too obvious I can give you yet another tip, fancier, unexpected, very fanzine.

For those lucky enough to live in or travel to Paris or London (and in both cities, the magazine is widely available) I know the perfect place: it is a picture gallery, the Baroque section, more precisely the rooms dedicated to the Prince of European painting of the 17th century: Peter Paul Rubens, who was born in Siegen on 28 June 1577 and died in Antwerp on 30 May 1640. For Parisians the target is Musée du Louvre, Richelieu wing, second floor, room 18, Galerie Médicis.For Londoners, the National Gallery (no excuse for Brits: free of charge), level 2, room 18.

There might be a few tourists hanging around in the room, maybe a sleepy visitor or a noisy school group, but large masses will skip these halls. Now, first flip through the pages of Whatevr #4, take a quick read of the articles, look at the pics, “hmmm, so these are the latest trends in fashion…” and then you will be ready to concentrate on Rubens. Ah, do not forget to make your selfie with the magazine in hand and the paintings in the background, that’s a must!

In the "Galerie" you will notice the gigantic paintings representing Maria de ' Medici, wife of Henry IV and mother of Louis XIII, both Kings of France, painted by the Flemish artist for the Palais de Luxembourg. Focus on one particular painting: The Arrival of Marie de ' Medici at Marseilles, I add, to join her new husband married by proxy in Florence a few months before. The work is impressive, the elegant Queen strides on a crimson drape adorning the bridge of the ship from which she is finally reaching her new home, her new reign. Now look down: three nude female figures of jubilant super-dynamic divinities appear like bitts ensuring the mooring line. Colossal nudities, beautiful and wonderfully abundant. Here are the nymphs, ideal of beauty and sensuality, glorifying the Queen of France by exposing their voluptuous nudity with total grace.

For those who live across the Channel, in London, well, the target is the National Gallery. Entering room 18 on the second floor, you’ll find The Judgement of Paris, particularly the version of 1632-35. The myth is famous, it’s the casus belli par excellence. Paris, Prince of Troy, must elect the most beautiful goddess of the Olympus. The three beautiful divas get naked to show their grace to the lucky judge. Venus will triumph, and the other two, Minerva and Juno, won’t take it so well. To thank the young judge for his vote Venus will help Paris to seduce and kidnap Helen, Queen of Sparta. Obviously, her husband Menelaus will not be too happy and it will be war, the Trojan war, the most extraordinary plot of the history of European literature.

Now, after having seen one of the two paintings. London or Paris, it does not matter, I am pretty positive that you are thinking something like “those nudes are too fleshy, too fat, it is an ode to cellulite rather than to beauty. Canon of Greek beauty? No way, those goddesses really need a good gym session.”

This might be true but keep anyway in mind that you are observing a painting by one of the greatest masters of all times, a true connoisseur of beauty: Sir Rubens.

The Olympic grace and beauty of those goddesses is shown in Rubens’ way (“Rubenesque”), with his traditional unsettling effect, powerful and dramatic, without hiding anything, and with plenty of colors and shapes.

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt - the scholar who invented the word Renaissance - so a man who knew his stuff pretty well - wrote that the art of Rubens would make the audience "wrapped and delivered by a giant wave, making it unable to carry out clear analysis". I find this fully true; when I look at Rubens’ paintings, I am always blown away, I never really know where to start looking. His naked buttocks of goddesses are very vigorous, plump and fleshy, maybe excessively, and undoubtedly extra-large, overweight. They have not much in common with the waif-like athletic bodies presently cluttering the media. We’ve got to be fair, plenty of cellulite, soft and plump thighs, quivering flesh, but also, I must say, a lot of exploding sensuality.

It is this beauty? Maybe yes, maybe no, but many people liked it and many are still pleased with it.

According to the painter Sir Rubens from Antwerp, the answer is certainly yes, and personally, I fully agree.

The fact that the ancient canon of beauty was different from the current one, is very well known and widely debated but that the Prince of Baroque painting saw that canon in such an abundance of “meat”, may be surprising.

The question of course is: why? There might not be an answer but certainly the topic is juicy and I am sure that browsing Whatevr in Rubens’ company may give you some true satisfaction.

Anyway, let’s try. Peter Paul Rubens is universally recognized as the greatest European painter of the 17th century. He was an indefatigable artist, an unsurpassed colorist, a creator of a brand and of a style appreciated by all European courts. He was a pleasant and intelligent man as well, enough to act as the confidant and diplomat for kings and princes, living in a century in which through art you could resolve wars and alliances, weddings and coronations. As a young man Rubens made a very long journey to Italy, basing his artistic education on the solid foundations of the Classical and Renaissance art as well as on his own Nordic tradition. His knowledge of ancient art and his brilliant understanding of the modern movements, together with every lack of fear for innovation, made him the perfect painter, the number one on the market.

In his tome De Imitatione Statuarum - About the Imitation of Ancient Statues - Rubens wrote: “it is necessary to follow the example of the antique sculptors, replacing however the stone of the statues with the living flesh”. He really believed that painters could be capable of capturing the qualities of the flesh but they had to avoid imitating the antiques, avoid imitating the material character of stone.

It is indeed true that his ideal of beauty derives from the Classics and he was certainly a great connoisseur of it. Furthermore, if we look at the Classical and Hellenistic art, curves of female bodies were far more pronounced than in our modern aesthetic ideal “skinny-size-zero”. But again, Rubens goes much further, he shows cellulite, “love handles”, softness. His female nudes once received and still do receive criticism, they are considered ugly, unhealthy, exaggerated. But at the same time those nudes are considered powerfully sensual as well.

At the National Gallery, London, in the room dedicated to Rubens, the no. 18, we can admire another panel that he painted in 1609-1610: Samson and Delilah. The story is well-known, the super sensual blonde Delilah seduces the poor hero Samson and gives him a tricky haircut, thus erasing his miraculous strength.

Now, after having seen one of the two paintings. London or Paris, it does not matter, I am pretty positive that you are thinking something like “those nudes are too fleshy, too fat, it is an ode to cellulite rather than to beauty. Canon of Greek beauty? No way, those goddesses really need a good gym session.”

This might be true but keep anyway in mind that you are observing a painting by one of the greatest masters of all times, a true connoisseur of beauty: Sir Rubens.

The Olympic grace and beauty of those goddesses is shown in Rubens’ way (“Rubenesque”), with his traditional unsettling effect, powerful and dramatic, without hiding anything, and with plenty of colors and shapes.

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt - the scholar who invented the word Renaissance - so a man who knew his stuff pretty well - wrote that the art of Rubens would make the audience "wrapped and delivered by a giant wave, making it unable to carry out clear analysis". I find this fully true; when I look at Rubens’ paintings, I am always blown away, I never really know where to start looking. His naked buttocks of goddesses are very vigorous, plump and fleshy, maybe excessively, and undoubtedly extra-large, overweight. They have not much in common with the waif-like athletic bodies presently cluttering the media. We’ve got to be fair, plenty of cellulite, soft and plump thighs, quivering flesh, but also, I must say, a lot of exploding sensuality.

It is this beauty? Maybe yes, maybe no, but many people liked it and many are still pleased with it.

According to the painter Sir Rubens from Antwerp, the answer is certainly yes, and personally, I fully agree.

The fact that the ancient canon of beauty was different from the current one, is very well known and widely debated but that the Prince of Baroque painting saw that canon in such an abundance of “meat”, may be surprising.

The question of course is: why? There might not be an answer but certainly the topic is juicy and I am sure that browsing Whatevr in Rubens’ company may give you some true satisfaction.

Anyway, let’s try. Peter Paul Rubens is universally recognized as the greatest European painter of the 17th century. He was an indefatigable artist, an unsurpassed colorist, a creator of a brand and of a style appreciated by all European courts. He was a pleasant and intelligent man as well, enough to act as the confidant and diplomat for kings and princes, living in a century in which through art you could resolve wars and alliances, weddings and coronations. As a young man Rubens made a very long journey to Italy, basing his artistic education on the solid foundations of the Classical and Renaissance art as well as on his own Nordic tradition. His knowledge of ancient art and his brilliant understanding of the modern movements, together with every lack of fear for innovation, made him the perfect painter, the number one on the market.

In his tome De Imitatione Statuarum - About the Imitation of Ancient Statues - Rubens wrote: “it is necessary to follow the example of the antique sculptors, replacing however the stone of the statues with the living flesh”. He really believed that painters could be capable of capturing the qualities of the flesh but they had to avoid imitating the antiques, avoid imitating the material character of stone.

It is indeed true that his ideal of beauty derives from the Classics and he was certainly a great connoisseur of it. Furthermore, if we look at the Classical and Hellenistic art, curves of female bodies were far more pronounced than in our modern aesthetic ideal “skinny-size-zero”. But again, Rubens goes much further, he shows cellulite, “love handles”, softness. His female nudes once received and still do receive criticism, they are considered ugly, unhealthy, exaggerated. But at the same time those nudes are considered powerfully sensual as well.

At the National Gallery, London, in the room dedicated to Rubens, the no. 18, we can admire another panel that he painted in 1609-1610: Samson and Delilah. The story is well-known, the super sensual blonde Delilah seduces the poor hero Samson and gives him a tricky haircut, thus erasing his miraculous strength.

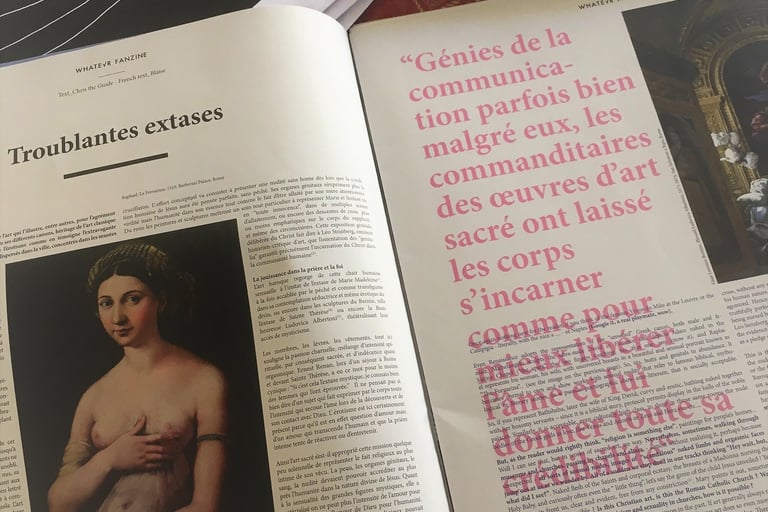

The Sacred and the Sexual

Whatever Fanzine NR.3, May 2017

by Chris the Guide

Our Western culture is comfortable with such an image, it is full of such images. In the Neoclassic period Napoleon had himself portrayed heroically nude by Antonio Canova as Mars the Peacemaker. This was a virtuous nude and did not convey vulnerability or embarrassment, on the contrary, it denoted strength and power.

As to female nudity, the message is clearly different; large breasts and curved bellies suggest fertility, procreation and abundance. With Praxiteles and his Venus of Cnidus, seduction was added, paving the way to the countless nymphs and sexy Venuses of ancient art, of which the Roman museums abound. Once again nothing new for the reader, if you think of the famous Venus de Milo at the Louvre or the Callipigia - literally, with a nice a…. - of Naples (Google it, a real playmate, wow).

Even Renaissance adopts the representation of the "unveiled" Greek canon, both male and female. Michelangelo sculpts the ultra-nude David in Florence and depicts Adam naked in the Sistine Chapel ("the spark", the two fingers touching, yes, that one, you know it), and Raphael represents his woman, his wife, with uncovered breasts in a beautiful and sensual portrait known as "The Fornarina"…. So, tits, butts and genitals in abundance. It becomes normal to own and show works with sensual nudity that refer to famous biblical, mythological or literary stories, in a pseudo pornographic show ante-litteram, that is socially acceptable.

But, as the reader would rightly think, "religion is something else", paintings for people’s homes… Well I can see that, but in works of sacred art, no way. Nevertheless, sometimes, walking through museums and churches, passing by chapels and altars, - almost without realizing it, perhaps because unexpected - all sorts of sensual nudes, images of "scandalous" naked limbs and orgasmic faces jump out at us as we wander by. All of a sudden we stop dead in our tracks thinking "Hey wait, but, what did I see?".

Naked flesh of the Saints and corporal ecstasy, the breasts of a Madonna nursing the Holy Baby, and curiously often even the " little thing", let’s say the groin of the child Jesus unveiled! Yes, it is there, in front us, clear and evident, free from any constriction[1]. Mary points it out, sometimes touches it. How is it possible? Is this Christian art, is this the Roman Catholic Church? Wasn’t nakedness sinful, embarrassing? Eroticism and sexuality in churches, how is it possible?

Often, what may appear strange to us now, was quite common in the past. If art generally always reflects the culture, the thought and the society of the time that produced it, religious art does so even more, being never just a decoration but having always intrinsically a liturgical and theological value. Therefore, in Christian art sexuality has necessarily a religious value. These works of art may not be there by mere chance.

The sense of it, although almost sunk into oblivion for centuries, exists and is connected to the innermost part of Christian faith. How handsome you are, my beloved! Oh, how charming! And our bed is verdant ... his left arm is under my head, and his right arm embraces me. (1,16; 2,6) Your graceful legs are like jewels, the work of an artist’s hands. Your navel is a rounded goblet that never lacks blended wine. (7,2) These are quotes from the Song of Songs, attributed to Solomon, Old Testament. The Song of Songs does not see the body as just sexuality or a vague heavenly metaphor, but it recognizes the body as the symbol that combines history to eternity, flesh and spirit, eros and love, skin and feelings, man and God (...). The beauty of man is total, circular, it ignores the distinction between body and spirit, the proclamation of the resurrection of Christ is the celebration of full harmony ... I quote Gianfranco Ravasi, Cardinal of San Giorgio in Velabro, President of the Pontifical Council for Culture, a distinguished biblical scholar and a man of great culture[2]. Beauty, aesthetics and love, quite simply man is beauty as created in the image and likeness of God and out of love he became man in Jesus. Therefore, love and humanity.

One can be Christian-Catholic or not, but certainly what is unique about this religious belief is the dual nature of Jesus, or rather the union of those two natures, divine and human, achieved perfectly in Mary's womb (Council of Ephesus 431 AD). It was not easy to accept that Jesus might be – equally - divine and human at the same time and this is one of the major and most debated mysteries of Christianity.

On the threshold of the Renaissance the divine nature of Jesus was generally accepted in Europe: he is represented in mosaics and altarpieces as the triumphant on the throne or alive and most divine on the cross, without any suffering. What was more difficult for the European culture of the time was to accept his human nature, his mortality, the fact that he truly could have died on the cross, that he had really agonized. Hence, in the nudity of Jesus there could be no shame because his human condition is truthfully perfect, without sin. His genitalia do not convey anymore virility but humanity. Similarly, being nursed by his mother indicates the human need to be fed, to appease hunger.

Leo Steinberg, an art-historian who first wanted to address these issues in our modern times, argues that the evidence of this deliberate exposure or ostensive unveiling of the genitalia of the Christ Child serves as a pledge of God’s humanation[3].

This is the reason why paintings and sculptures lavished particular care in representing Mary and the nude Child, Mary nursing Him, the Deposition and the Pietà – that is the corpse of Jesus - or the Circumcision.

The importance of human flesh and sensuality are also to be found in sublime Baroque works, both in the ecstasy of Mary Magdalene, where the beautiful “Santa” oppressed by sin and in ecstatic contemplation often appears very seductive, sensual and somehow erotic[4], or in famous sculptures by Bernini such as Saint Teresa[5] and the blessed Ludovica Albertoni[6], still displayed in two Roman churches, where the saints are theatrically portrayed in mystical ecstasy.

The limbs, lips and the clothes convey a carnal passion, waving unbelievably between sacred mysticism and orgasmic indecency. A cynical French, Renan, visiting Rome, and observing Saint Teresa commented: "Si c'est cela l'extase mystique, je connais bien des femmes qui l'ont éprouvée”. Perhaps he understood everything, or maybe nothing ...

Eroticism is certainly present, but its essence is dramatically religious and spiritual, the artist wants to show the divine love, enormously more powerful than human love, exploding in the body almost consumed by a rapture of uncontrollable euphoria. Art had the mission to declare solemnly these religious movements. Flesh and genitals, blood and nudity were there to represent the true humanity of Jesus, the image of Christ the Man-God. The manifested feminine sensuality of mystic women, through the evidence of a physical passion, wanted to highlight the drama taking place in their hearts, in their souls. The power of the images was to show God’s love and humanity, or better God's love for mankind. If sexuality in religious art was not taboo and had nothing frivolous, there had to be a reason. And this is the reason.

[1] Among the most famous: Madonna and Child by Antoniazzo Romano, 1487, Palazzo Barberini, Rome

[2] Ki Tob: "Dio vide che era bello, Biblia, 1992

[3] The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, 1983

[4] For example a famous Mary Magdalene by Guido Cagnacci, 1625-27, Barberini Palace, Rome

[5] in the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Cornaro Chapel

[6] in the Church of San Francesco a Ripa, Altieri Chapel

In Italiano su Isidora

Rome is “amor”, Rome is art and art is undoubtedly “amor”, love, love for beauty. Strolling through the streets of downtown Rome literally means being surrounded by beauty. Streets, squares, churches, museums, sun, colors are an ode to beauty. The concept of beauty, theorized by the aesthetic philosophy in the 18th century, is a pillar of the classical Greek-Roman art and often shows sensuality and eroticism; just think of the various female and male nudes visible in the museums of the city, even in its sacred heart: the Vatican.

The church and the brotherhood of S. Maria dell’Anima.

Rome

Short history of the building.Short history of the building.

The origins of the church of S. Maria dell’Anima can be found around the jubilee year of 1350 when the papal guard Johannes Peter from Dordrecht and his wife Katerina bought some houses to be used as an hospice for “the health of the body and soul” of pilgrims and sick people coming from the “nation Alamannorum”.

According to Schmidlin[1] the hospital of St. Andrew, which was founded at the end of the 13th century to help the German poor, later converted into a women hospice, was soon absorbed by the Dordrecht’s hospice. In 1399 the brotherhood obtained papal approval of pope Bonifatius IX and soon became a fraternity with statutes. The name of the church derives from the discovery of an ancient icon of the Virgin with two praying souls which was found in the area. To commemorate the event, in the tympanum of the portal a sculpture can be seen representing the Virgin Mary invoked by two souls in purgatory.

The figures, traditionally ascribed to Andrea Sansovino, are in fact a later copy by Lorenzetto, perhaps assisted by Raffaello da Montelupo.

The first enlargements of the buildings, paid almost completely by Koenrad de Hal from Brabant, seem to go back to the ‘30 of the 15th century, and were directed by an architect of Siena, maybe Pietro Pisanelli, who gave to the building a gothic aspect. The construction site was closed in 1446.

In 1499, in view of the Jubilee, the reconstruction of the church was decided by three important German citizens: the Master of ceremonies Johann Burchardt, the Rota notary Sander (in 1508 also his own house next to the church was completed, and to be donated to the brotherhood after his death), and Wilhelm van Enckenvoirt, later a cardinal very close to Pope Adrian VI. Although the gothic complex was not falling apart at all, it was decided to build a new church, following the examples of other nations who where constructing churches and hospices following the modern Renaissance style. The hospice’s administrators asked advice to Bramante, Andrea Sansovino and Giuliano da Sangallo. The 11th of April 1500 the first stone was placed with the blessing of the Archbishop and sponsored by Emperor Maximilian I. The works were going fast, and the rebuilding and demolition were carried out simultaneously. In 1510 the main altar was consecrated. The next year, following Sangallo’s project, the building of the façade was started and between 1516 and 1518 the constructions ended with the construction of the bell tower.

The church was strongly raped by the “lanzichenecchi” during the Sack of Rome in 1527 and suffered other damages during the short adventure of the Roman Republic. During the French Revolution many valuables disappeared from the church and the hospice. After this the church became mainly Italian until 1859 when the emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria had the statutes rewritten and the College was founded.

In 1906 finally the Anima became officially the National Church of the German speaking Catholics.

The brotherhood through the centuries.

According to the old statutes of the Anima, valid until the end of the 17th century, the management of the brotherhood and the hospice was carried out by four “Provvisori”. To become a member they had to donate on a regular basis a certain sum of money and a legacy was expected. From this income the houses were financed, where pilgrims, both men and women, used to get free board and accommodation for three to four days[2]. Sufficient funds were left to make the hospital into “the best hospital of Rome”, as Martin Luther wrote in his diary during a visit to Rome.

As mentioned earlier, in 1399 pope Bonifacius IX, together with the papal eapproval, gives the foundation the status of brotherhood with the name of “S. Maria dell’Anima” . Later he grants special indulgences to those who decide to help with the building of the hospice, especially after the large donations of Teodorico[3] (or Dietrich) of Nyem, first rector of the hospice, Papal notary in Avignone, later also abbreviator and scriptor at the Cancelleria with Gregorius XI. He died in Maastricht in 1406.

With two documents of May and June 1406 Pope Innocent VII puts the brotherhood under papal protection, making it exempt from charges and obligations to other municipal or ecclesiastic institutions. The Pope also grants the Anima the right to bury their death on their grounds, which is a useful source of income. With the bull of December 4th,1444 of Eugene IV the brotherhood receives the right to administer sacraments to their countrymen exactly like a real parish: S. Maria dell’Anima becomes officially the church of the Empire’s subjects.

How should we explain this instantaneous success, considering the difficult situation of the Roman Church after the Western Schism and also taking into consideration the presence of the much older brotherhood of “S. Maria della Pietà in Camposanto dei Teutonici e dei Fiamminghi” which had more or less the same activities. The answer can be found in the fusion of the Anima, shortly after the grant of the Dordrecht couple, with the “Confratria Alamannorum”, which had developed in Avignon. The majority of this brotherhood’s members where born in the “Nederduitsland” i.e. the part of the Empire including Holland, Belgium and the German Low-Rhineland. Coming back to Rome in 1377 the Pope is attended by some members of the “Confratria Alamannorum”, brotherhood that always remained faithful to the roman faction.

From the beginning the Anima does not seem a typical German organization, especially if we consider the present Germany borders. The Dutch seem to play an important role, even more with the rise of Protestantism in Germany and also because of the fact that the church became the bury-place for Pope Adrian VI, who gave in his short reign many benefits to the brotherhood. This Dutch lead of the foundation is confirmed by a census of the members in 1585-1586: 55 members were Belgians, 44 where Dutch and only 6 came from the lands of Westphalia.

In 1599, after the death of Philip II, during the Dutch War of Independence, the Flemish were thrown out and after the Treaty of Rijswijk also the French Alsatians had to leave. With these events once and for all the Dutch hegemony of the Anima institutions draws to an end.

For more than four centuries the brotherhood will survive under the protection of the Habsburg family, starting with Ferdinand’s election in 1556 until the fall of the Empire in 1918. An imperial edict of 1824 limits the membership only to the citizens of the Empire, of any language. The fact that the Empire was supranational brought in many non-German speaking members, especially Hungarians and Italians. During the 19th century, when part of northern Italy was under Vienna’s control, the Italian-speaking members were so many that during a visit to Rome the Emperor realized that not even one priest could speak German! In 1859 Pius IX reorganized the brotherhood: the membership had to be open to any catholic believer who was part of the German Confederation. The Emperor kept however, together with the Curia, the right to elect the Rector. In 1906 the Anima becomes officially the parish church of the Germans in Rome.

Pope Johannes XXIII reorganizes the foundation once more. The Austrian bishops, together with the German bishops obtain the right to elect the Rector. The archbishop of Köln chooses the priests of the German Parish in Rome. A catholic Dutchman has to be member of the administration, the chair is usually reserved to the rector of the Dutch College.

The church.

Taking a right turn after leaving piazza Navona trough via S. Agnese in Agone, We will be in via S. Maria dell’Anima, after a few steps we will see the elegant Renaissance facade of the German church: S. Maria dell’Anima with on the right hand side of the building the beautiful bell tower with double lancet windows and colored majolica, whereas the pinnacles and a conic cusp on the top are an example of gothic stile on a Renaissance building.

Entering the church we sense immediately a non-Roman atmosphere: the three naves have the same vertical height, typical device of the German Hallenkirchen. On the main altar there is the famous Fugger Altarpiece, painted by Giulio Romano in 1523ca. The painting represents a Holy Conversation. The Madonna and Child are in the middle with three little angels, with on the sides images of St. Mark, St. Joseph, St. Jacob and St. John as a child. The setting has a classical taste and reminds of Vitruvius studies, Vasari talks about a “casamento che gira ad uso di teatro[4]”. On the back an old spinning woman comes out of a little door, close to her a hen and her little chicks are perking up the landscape. On the right hand side we see the monument of Pope Adrian VI (1522-1523), conceived by Baldassare Peruzzi with marbles made by Michelangelo Senese and Tribolo. Adrian Florensz, son of an Utrecht’s carpenter, later Charles V’s tutor, has been the last non-Italian Pope before John Paul II. Shortly after his election, on his way from Spain to Rome,. He immediately took the first steps for church reform. During his short pontificate he tried to reform the Curia and blocked many artistic works except the Fabbrica of S. Pietro .He was not at all fond of Humanists and Poets like Leo X before him. Speaking about the Laocoon, found some years before in the Domus Aurea, he said that is was a “useless image of pagan idols”, he even thought about plastering Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, scandalized by all that nudity.

Adrian’s tomb was commissioned by Cardinal van Enckenvoirt, also buried in the Anima church. His monument, made by Giovanni Mangone or maybe by Michelangelo Senese, is placed on the right side of the main entrance. On the sides of the aisles the are eight chapels, four on each side. The first chapel on the right, the St. Bennon chapel, gives hospitality to a painting (1618) by Carlo Saraceni representing the saint receiving from a fisherman the keys of Meissen’s Cathedral, found in a fish belly. After that, the chapel of St. Anna has on the altar a Holy Family by Giacinto Gimignani, on the right of it we can see the tomb of Cardinal Sluse (+1687) with a bust made by Ercole Ferrata. The third chapel is known as the St. Mark chapel, or better as the Fugger chapel, it was paid by the famous bankers family known for their close friendship with the Habsburgs. The walls are painted in fresco by Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta with stories taken from the Life of the Virgin Mary (the frescoes are dated either 1550ca. or 1560-63). On the altar a crucifix by G. B. Montano (1584) replaces Giulio Romano’s painting, moved in the 16th century to the main altar of the church. A Pietà very similar to the one made by Michelangelo for St. Peter is placed in the fourth chapel of the right aisle. It was begun by Lorenzetto and completed by Nanni di Baccio Bigio.

In the left aisle on the third pillar is the tomb of Ferdinando van der Eyden (+1630) made by F. Duquesnoy. The first chapel on the left, like St. Bennon’s in front, hosts a painting by Carlo Saraceni (1618) representing the Martyrdom of St. Lambertus; the next chapel, dedicated to St. John Nepomucenus is decorated by Ludovico Seitz at the end of the 18th century (Seitz is also the author of the Saints painted on the central nave’s vault). The chapel of St. Barbara, the third one, commissioned by Cardinal W. van Enckenvoirt, has on the walls stories of the saint made by the Dutch painter Michael Coxcie. The fourth chapel is decorated with wonderful mannerist frescoes (1530 ca) painted by Francesco Salviati. Particularly noted is his Deposition of Christ placed on the altar.

It is also possible to get into the church passing trough the German College’s entrance at number 20 of piazza S. Maria della Pace. Once entered we can admire a beautiful cloister full of antique marble, crossing it we can get into the sacristy were on the vault is painted an Assunta by G. F. Romanelli (1636), on the side there is a rare example of 15th century wood sculpture of the German School representing a Madonna with St. Anna and the Child.

[1] Schmidlin Joseph, Geschichte der deutschen Nationalkirche in Rom : S. Maria dell'Anima, Wien, Freiburg im Breisgau, 1906.

[2] The documents about the brotherhood and its buildings did not suffer of many deprivations and are easily found in Fiorani Luigi, Storiografia e archivi delle confraternite romane. Ricerche per la storia religiosa in Roma, Edizioni di storia e letteratura, Roma, 1985, pp.175-413.

[3] The brotherhood after his death receives an inheritance of 7 buildings.

[4] Vasari Giorgio, Le Vite dei più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architetti, Ed per il Club del Libro, 7 volumi, Milano 1964-1966 (Firenze, 1568), volume V, pp. 273-272

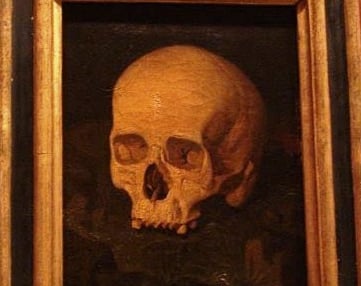

The Horrifying Story of Goya's Skull

Gaya Nuño (Italian edition: La orripilante storia del teschio di Goya, Skira, Milan, 2010) wrote this extraordinary little book in 1966, recounting the equally extraordinary and incredible adventure of the mortal remains of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya y Lucientes.

A story so fascinating that it convinced me to publish a small summary of the events.

And the head?

In 1928, the centenary of his death was celebrated, and on April 17, Don Hilario Gimeno announced, to the astonishment of those present, that he had found in an antique shop in Zaragoza an oil painting depicting the lost skull:

“Cráneo de Goya, pintado por Fierros, 1849.”

How and why he came to possess it remains a mystery.

It is believed that the skull of the genius underwent a horrific yet marvelous adventure—fitting for a genius. But let us proceed in order.

One night—perhaps rainy, certainly dark—three men ventured into the cemetery to carry out an unusual theft: to steal the skull of the genius.

And why? For adventure, for art, and for… science.

Or rather, for pseudoscience: a theory known as phrenology, which claimed to diagnose virtues, vices, inclinations, and qualities through the observation and measurement of the skull, divided for that purpose into imaginary compartments.

Zone 26—the seat of intellectual faculty for perspective and color.

Zone 18—home of “wonderfulness.”

Zone 19—imagination.

Zone 20—the spirit of satire.

Qualities that Goya possessed in abundance; what better skull to determine the perfect dimensions of such cerebral regions?

Nonsense, of course—but it is certain that in the period when the glorious painter’s corpse was decapitated, people believed in such things blindly.

Thus, it was a decapitation for science!

A doctor—a phrenologist—studied it, but his companion in the adventure, a painter, kept the relic, perhaps by a law of nature—an object of ultimate inspiration.

Dionisio Fierros kept it among his dearest possessions (though, it must be said, it did not help his inspiration much, as proven by the poor and utterly uninspired quality of his forgotten paintings).

So, where is the skull now?

And here we reach the most painful part: the skull is destroyed.

It was the painter-grave-robber’s own son who, unknowingly, committed the deed.

A medical student, after his father’s death, he found the object without knowing its origin.

It could have been the skull of a simple peasant—and for a medical student, to have a skull all to himself was quite a luxury. Nothing wrong with that—if only he hadn’t had the brilliant (ah, youth!) idea of experimenting at home with his colleagues on the “power of germination.”

They filled the skull with damp chickpeas and waited 24 hours to see the effect.

The effect was indeed that of “the power of germination,” a rather banal natural process.

The chickpeas swelled and… the worst happened. The skull exploded.

Experiment successful. The bones were shared among those present.

“Goya’s skull is not lost, but transubstantiated into all our brains, as in a sorcerer’s mortar,”

wrote Ramón Gómez de la Serna on the matter, in his pompous yet effective style.

A fitting end for such an imaginary, dark, brilliant, and terrible head.

He was, after all, and solely he, in art, the greatest tamer of witches, harlots, and corpse-raisers.

A biography turned into a necrology; a skull stolen for an imaginary science darker than his darkest paintings; a skull destroyed for a childish game.

As in life he scattered colors and lines ablaze with shadowed passion, so in death he scattered the “minutiae of his mighty bones.”

In the end, writes Gaya Nuño,

“Few of us can claim that three fanatics, alone at night in a romantic cemetery, might steal our head.”

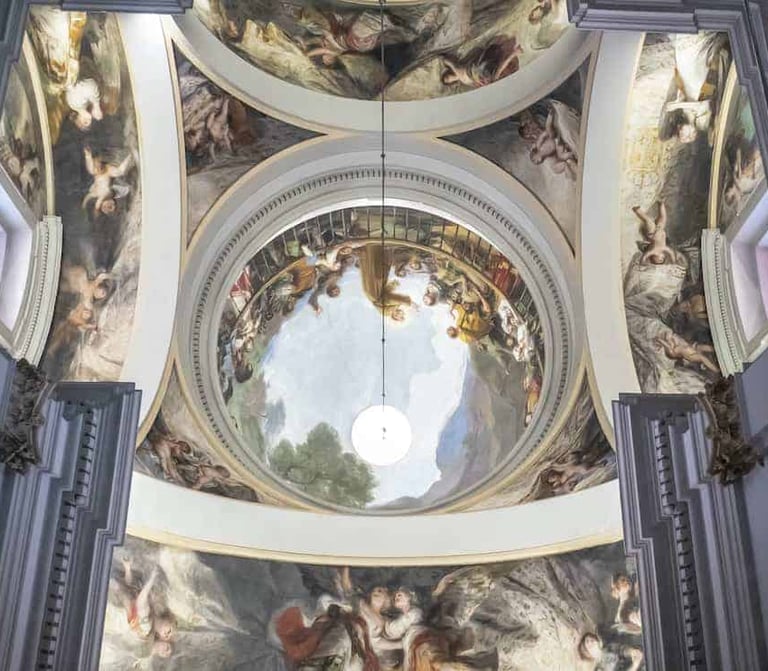

We entered the church. Small, tiny, yet worthy of a Cathedral. A Cathedral—what am I saying?—no other in the world enjoys such a glorious mantle of color, nor such a surprising dome, with all those little creatures—unaware and observant, detached and attentive, some beautiful and others sinister—that Goya depicted around the miracle of Saint Anthony of Lisbon.

He decorated that tiny, popular cathedral, granting only minimal space to the saint and far more to the spectators.

A free and eclectic mixture—memories of Correggio and of Parma known in his youth, but also prophetic forebodings of later painting: Delacroix, Nolde, Rouault, even Bacon.

Exactly beneath the dome, a plaque declares that this is Goya’s final resting place—at least so we believe.

There lie the bones of the tremendous painter, creator of so much wonder.

But not the complete skeleton—the skull is missing!

For the most terrifying of Goya’s caprices was the one that, posthumously, starred his own head.

Curious, indeed, that rarely in the history of art has there been a man so attuned to the witchlike and the demonic as Goya.

He was struck by a grave illness, the nature of which was never clarified—perhaps a severe form of hemiplegia—that caused him to lose his hearing almost completely.

Deaf and solitary—a solitude that breeds darkness, that breeds monsters. Like the sleep of reason that breeds monsters.

Famous are his sarcastic and burlesque Caprichos and other etchings he called Proverbs and Follies.

An imagination without rest, which reached its darkest point in the decoration of his country house near the Manzanares—the Black Paintings of the Quinta del Sordo, “black” for the shadowy dominance of malignant and perverse creatures, forces that would ultimately turn against the very head that had created them.

He died in 1828, during the night between April 15 and 16, in Bordeaux.

Buried in the Chartreuse Cemetery, he remained in oblivion until 1878, when the Spanish consul in Bordeaux—newly widowed—buried his wife in the same cemetery and saw the painter’s grave in a state of ruin and neglect. He took an interest in the matter.

Years later, he finally succeeded in convincing the state to intervene—the painter deserved better, a tomb in his homeland, perhaps in the Sacramental Cemetery of San Isidro.

So the tomb was opened and…

Upon opening it, we found in a zinc coffin the painter’s bones—“except for the head, which was completely missing.”

“Since the coffin did not appear ever to have been opened, we were led to believe that Goya had been buried already decapitated—perhaps by a doctor, or by some mad lover of rarities.”

The transfer of the remains dragged on, not least because the Spanish government refused to pay for the operation, which amounted to the paltry sum of 1,400 francs.

Only on May 11, 1900, did the bones finally arrive in Spain and were laid to rest at San Isidro.

It was then decided, most fittingly, to move them once again to the place where they still lie—though without the head—beneath the dome of the Florida.

That was November 29, 1919.

A Brief History of the Nativity Scene in Italy

Essay by Christiaan Santini for the exhibition “Kerstgroepen wereldwijd” (Nativity Scenes from Around the World), November 2009 – January 2010, Museum Timmerwerf, De Lier, The Netherlands.

Amid the glittering splendor that surrounds the modern Christmas—today a consumerist feast of Western culture, globally adopted yet rooted, it is worth recalling, in a Christian religious tradition—the presepe (Nativity scene) remains one of the few popular customs that still evokes the birth of Jesus. In churches and homes alike, the little figures are brought down from attics, freed from dusty boxes, and arranged according to a layout repeated each year. They offer an image of the event that Christmas recalls and makes present again: a distant happening in time—the birth of the Child.

The word presepe derives from Latin forms such as praesepe or praesepium (from prae = “before” and saepes = “enclosure,” meaning “a place before the enclosure”)—that is, a “crib” or “manger.” Thus, the manger where, according to tradition, Mary of Nazareth gave birth to her son. It is commonly told in Italy that the first to reenact this sacred event—this Epiphany (manifestation)—was St. Francis of Assisi, who in December 1223 at Greccio in Umbria staged a sacred representation of the Nativity, using local peasants as actors playing the protagonists of that holy night: Jesus, Mary, Joseph, the angels, and the shepherds. The episode was later depicted by Giotto in the Upper Basilica of Assisi.

From this almost theatrical experience, which immediately became famous, grew the custom of recreating the sacred moment of the birth each year, first with real people and later with statues and figurines. St. Francis’s intuition was both great and somewhat radical: to relive the event and show it to ordinary people as something natural—a birth—and to do so in the countryside, far from the splendor of churches, understandable and magical even to those unfamiliar with Scripture or Church tradition.

The history of the presepe, however, has even more ancient roots. In pagan religions, the natalis (from natalis = “pertaining to birth”), fixed on December 25, celebrated the birth of the Sun, later identified with the god Mithras. In preparation for that day, children would polish small terracotta statuettes representing their ancestors, placing them imaginatively within an enclosure. On Christmas Eve, the family gathered to invoke the protection of their ancestors, leaving them bowls of food and wine. The next morning, in place of the offerings, sweets and toys were found—brought, it was said, by the grandparents and great-grandparents. Though dead, the event confirmed that their souls continued to protect and watch over the family.

The similarities with modern Christmas traditions are striking. Christianity, so to speak, absorbed and reinterpreted these customs. Numerous representations of the Nativity appear in Christian art already a century after Christ’s death—in the catacombs and on sarcophagi. But in the 7th century, under Pope Theodore, the Nativity assumed a more concrete form. In Rome, in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, an oratory entirely dedicated to the presepe was built. The oratory, known as Santa Maria ad Praesepe, traditionally housed an important and curious relic: the Holy Crib itself. In this very place, between 1290 and 1292, Arnolfo di Cambio sculpted the first fully three-dimensional statues depicting the Nativity (some of which are still preserved there).

The first complete Nativity scene known to have existed, recalling the representation of Greccio, was set up in Naples by the Poor Clares in the church of Santa Chiara. The custom continued to evolve until its official recognition in the 16th century when, thanks to the decrees of the Council of Trent—which encouraged sacred representations throughout the Catholic world—the presepe was acknowledged for its powerful capacity, still central today, to convey faith in the events of the Nativity in a simple, accessible way for the people.

The golden century of the presepe was undoubtedly the 18th century, particularly in Naples (though renowned examples also come from Puglia, Liguria, and Sicily). The great noble families competed with one another to create astonishing Nativity scenes in their palaces, inviting the public to admire them and to judge which were the most beautiful and elaborate. The figurines were true works of art, dressed in the finest fabrics and adorned with real jewelry. Even the Bourbon royal family spent vast sums commissioning Nativity scenes for their salons.

This flourishing “genre art” quickly evolved. The imagination of skilled artisans introduced mechanical and hydraulic devices, painted backdrops, and figures drawn from contemporary Neapolitan life. The Nativity scene became increasingly a pretext for depicting bustling city life, in which the holy figures mingled with merchants, soldiers, peasants, and all sorts of townsfolk. Every class of 18th-century Naples could see itself represented—in the markets, inns, and narrow streets—miniaturized and naturalistic, inspired by the landscapes of Campania. Though anachronistic, these details vividly capture the atmosphere of 18th-century Naples—its colors, flavors, and scents.

The Charterhouse of San Martino in Naples today houses the oldest and most complete collection of Neapolitan Nativity scenes in the world—an incredible journey through the city’s popular devotion and artistry. A colorful, picturesque, and beautiful Christmas, open all year round! As Michele Cuciniello, perhaps the greatest Neapolitan presepista, once said: “The Neapolitan Nativity is a page of the Gospel written in Neapolitan dialect.”

The tradition of recreating scenes of everyday life “updates” itself each year: the clergy, nobles, bourgeoisie, and commoners of past centuries are now joined by modern figures engaged in their daily occupations. One may find politicians, footballers, and television personalities alongside the canonical characters—Berlusconi beside the shepherds, Cannavaro (Naples’ own captain of Italy’s national team) raising the World Cup in a tavern, while the Magi approach the manger outside. Today’s soldiers and police stand beside their Roman predecessors, ensuring order. Every eccentricity is permitted, provided the sacred place of the birth is respected and the anachronism remains humorous, never irreverent.

The central thread, however, remains deeply religious, as Pope John XXIII summarized in 1962:

“May a ray of grace reach everywhere—the grace, the light of the Grotto of Bethlehem, the song of the Angels, the maternal care of Mary, the protection of Joseph; and may for every man arise, in purity and perfect harmony, the beginning, the renewal of true joy brought to earth by the Son of God.”

The sacred scene—the miracle of God made man—must remain essential and central. Curiosities and eccentric details may tell of their own time and its people, with their virtues and vices, but the focus must remain on the mystery of the Incarnation.

The sacred meaning of the presepe deserves deeper explanation. The representation of the Nativity scene is not merely evocative; it is rich in symbolic meaning, with a long and multifaceted tradition. The scene is based mainly on the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, the first to describe the Nativity. Mary and Joseph were in Bethlehem for a census decreed by the authorities. Luke recounts that Mary “laid her child in a manger, because there was no room for them at the inn.” He also tells of the shepherds’ annunciation and of the Magi from the East, guided by a star, who came to adore the newborn King.

Here the canonical Gospels stop; other details and figures derive from apocryphal texts and the writings of the Church Fathers, which enrich the scene with symbolic and allegorical meaning. The names of the three Magi—Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar—come from the Armenian Gospel of the Infancy. Their number, fixed at three by St. Leo the Great, was variously interpreted: as representing the three races of humanity (Semitic, Japhetic, and Hamitic), the three known continents (Asia, Africa, and Europe), or the three ages of man (youth, maturity, and old age). Their gifts reflect Christ’s dual nature: myrrh, used in embalming, represents his human nature and foretells his sacrificial death; incense, rising toward heaven, symbolizes his divinity; and gold is the gift reserved for kings.

Although the Gospels mention the manger, they do not specify its location. The Basilica of the Nativity in Bethlehem stands over the site traditionally identified as the grotto of Jesus’s birth; the apocryphal Gospels also refer to a cave. Likewise, the god Mithras—the sun—was said to have been born in a cave, and his birth was celebrated on December 25!

The ox and donkey are not mentioned in the Gospels either; they come from a prophecy of Isaiah, who rebuked the Jewish people for being deaf to God’s word and contrasted them with the meekness of the ox and the donkey. Origen later interpreted them as symbols of the Jewish and pagan peoples—for whom redemption was begun. The dual nature of Christ appears again in the contrast between angels, creatures of the heavenly world, and shepherds, symbols of humanity in need of salvation.

Even colors hold meaning: the Virgin’s blue mantle symbolizes heaven; white represents purity; red, human nature and the blood of sacrifice. Joseph, often depicted in shadow and wearing muted colors, represents humility—the attitude with which man, the sinner, must approach God.

These are only a few examples of the rich symbolic complexity of the Nativity scene, which, though it appears simple and natural—a birth, albeit divine—embodies profound theological meaning.

Over the centuries, even the minor characters of the modern presepe have acquired symbolic value. The inn represents vice and sin; the caricatured townspeople symbolize the moral failings of every social class. The viewer recognizes himself in them—torn between pleasure in being represented and shame for his own weaknesses. Among them, one might even find a drunken priest or a clergyman surrounded by the flames of purgatory—since even the clergy are not free from sin! (Curiously, high-ranking clergy and nobility were never represented in the Neapolitan Nativity, offered by the wealthy as a spectacle to the common people—there was room only for the vices of the poor!)

The devil, often near the crib, foreshadows Christ’s temptations in the desert. Soldiers prefigure both the Massacre of the Innocents and obedience to authority. Souls in purgatory appear, surrounded by flames, awaiting salvation. The interpretations are multiple and not mutually exclusive—each adds new layers of meaning.

The Nativity scene exhibited here represents a typical family collection: all the canonical figures are present, but alongside them stand popular figures, born of imagination rather than Scripture, capturing the vitality of folk tradition.

This open-air theater of puppets and caricatures is, in a sense, a “play within the play.” After all, the presepe itself is closely related to theater—it seeks to make a distant event immediate through realistic staging. The Nativity scene is not a sacred icon, but a joyful and scenic re-evocation of a sacred and joyful event: the birth of Christ.

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Contacts

Mail me:

christiaansantini@gmail.com

info@christheguide.com

Or WhatsApp me:

+39 347 8769063