The Greatest Archaeological Discovery in Dutch History Is in New York

The story of one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the late 20th century begins in May 1991 in New York, at 290 Broadway, in the heart of Manhattan.Bones began to emerge — in large quantities. Their nature soon became clear. In fact, their possible presence was already suspected: there had once been an old cemetery on that site, a cemetery for enslaved Africans, used between 1630 and 1795. Over two hundred years had passed, and most assumed it had vanished amid the transformations of the modern metropolis. Yet, about ten meters below ground, it resurfaced: the African Burial Ground.

3/12/20244 min read

The story of one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the late 20th century begins in May 1991 in New York, at 290 Broadway, in the heart of Manhattan. Construction had just begun on a massive project: a new skyscraper, the Federal Office Building, with an estimated cost of $276 million. But the building would never be completed. During excavation for the foundations, bones began to emerge — in large quantities. Their nature soon became clear. In fact, their possible presence was already suspected: there had once been an old cemetery on that site, a cemetery for enslaved Africans, used between 1630 and 1795. Over two hundred years had passed, and most assumed it had vanished amid the transformations of the modern metropolis. Yet, about ten meters below ground, it resurfaced: the African Burial Ground.

It was an extraordinary stroke of luck. The remains were remarkably well preserved, thanks to the fact that in the late 18th century, before the cemetery was abandoned, it had been covered by some seven meters of earth and debris during a yellow fever epidemic — a protective layer not unlike the volcanic ash that preserved Pompeii. Construction halted, and archaeology took over.

What emerged was a necropolis containing the remains of over 15,000 individuals. As excavations continued, the magnitude of the discovery became clear: not only the largest African cemetery ever found in the United States, but also a crucial testimony to the origins of New York. An ancient American cemetery, a cemetery of enslaved Africans, in Manhattan, New York!

One might exaggerate and say that the great cultural capital of the Western world is literally built on a foundation of slavery and oppression. Perhaps it is an exaggeration, a provocation — but there is some truth in it. The role of slavery in the development of the New World, even in the North, is well known but often underestimated, due in part to the long-standing myth of the North as the anti-slavery champion against the slaveholding South.

The milestones are familiar: Independence on July 4, 1776; the first abolition laws starting in Vermont in 1777; then the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery on December 18, 1865. But what about before 1865? What were conditions like for enslaved people in Manhattan under Dutch rule, then under the English, and in the early years of the United States? The discovery of the African Burial Ground has opened a new chapter in this story, forcing us to reconsider and re-examine with new — tragic and invaluable — evidence the history of New Amsterdam and New York.

I should pause here. Perhaps, as a white person and half-Dutch, I have no right to tell this story. I apologize for choosing to do so, with honesty and some shame. Yet this is also the story of an extraordinary discovery, an archaeological miracle, a priceless new historical source — and today, a museum that deserves to be visited as much as MoMA or the Met. So I will go on.

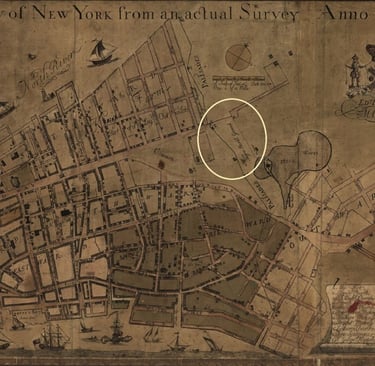

To understand the importance of the African Burial Ground, we need to step back to the origins of New York, when it was still New Amsterdam. Founded in 1625 as an outpost of the Dutch West India Company, the city received its first Africans in 1626: eleven men captured from a Portuguese ship. We even know their names, which were geographical in nature: for example, Paulo Angola, Simon Congo, Ian Fort Orange. Eleven enslaved Africans among a population of 300.

The Dutch slave system differed from the English model that would follow. Though required to pay a tax to the Company, Africans enjoyed a form of semi-freedom: they could own houses, farm land, sell produce, and access the courts. This allowed the development of an active African community that contributed to building key infrastructure such as Fort Amsterdam, the defensive wall that gave its name to Wall Street, Broadway, and other features of the nascent city. In short, while still forcibly uprooted and enslaved, Africans in New Amsterdam played an active role in shaping the new colony, with duties but also limited rights. To be clear, this does not absolve the Dutch Republic of its immense responsibility for the history of slavery: the guilt is indelible, a wound to be remembered as a permanent scar.

Around 1650, this community was granted a plot of land for burials — thus was born the African Burial Ground of Manhattan.

But in 1664 everything changed. The English arrived, and New Amsterdam became New York, named for the Duke of York, James Stuart, brother of King Charles II — himself a major shareholder in the Royal African Company, a slave-trading enterprise. Under English rule, conditions for Africans deteriorated drastically. The relative freedoms of Dutch times were replaced by increasingly oppressive measures, such as the appointment of a “Whipper of the Slaves” and severe restrictions on funeral ceremonies. New York also became a central hub of the slave trade, in stark contradiction to its later image as a symbol of liberty. The cemetery was closed at the end of the 18th century and disappeared from maps — until 1991, when plans for a new skyscraper uncovered it once more, in exactly the wrong (or perhaps the right) place.

In 2003, the remains were honored in a solemn ceremony, and the area was declared a National Monument. Today, the African Burial Ground is not only an archaeological site, but also a place of memory and reflection.

This discovery marked a turning point, not only for the history of New York, but also for public archaeology. During the first stages of excavation for the Federal Office Building, techniques were rushed and disrespectful: the goal was to move quickly and continue with the skyscraper project. But this risked erasing forever a crucial part of the city’s history. The African American community quickly realized this and, through protests and heated debate, forced a change of course. The skyscraper would not be built.

The excavation was placed under the direction of Michael Blakey, a serious and highly respected African American anthropologist — a symbolic choice, restoring dignity to those who had been forgotten too long. More importantly, the work was done properly. Thanks to a careful, respectful approach, archaeologists recovered an invaluable heritage. The remains revealed not only malnutrition and abuse, but also African funerary practices and cultural traditions that had survived deportation.

Though shocking to New York’s multiethnic community, these stories are a treasure trove, reshaping the history of the city and its inhabitants. A trace of the past that inspires both shame and pride, awareness and surprise. A testimony, a reaffirmation of collective memory that — thanks to archaeology and the determination of the African American community — has become a necessary monument, a global archaeological heritage that enriches New York, and all of us.

The greatest archaeological discovery in Dutch history

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Contacts

Or WhatsApp me: