The Horrifying Story of Goya's Skull

Gaya Nuño (Italian edition: La orripilante storia del teschio di Goya, Skira, Milan, 2010) wrote this extraordinary little book in 1966, recounting the equally extraordinary and incredible adventure of the mortal remains of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya y Lucientes. A story so fascinating that it convinced me to publish a small summary of the events.

12/12/20175 min read

We entered the church. Small, tiny, yet worthy of a Cathedral. A Cathedral—what am I saying?—no other in the world enjoys such a glorious mantle of color, nor such a surprising dome, with all those little creatures—unaware and observant, detached and attentive, some beautiful and others sinister—that Goya depicted around the miracle of Saint Anthony of Lisbon.

He decorated that tiny, popular cathedral, granting only minimal space to the saint and far more to the spectators.

A free and eclectic mixture—memories of Correggio and of Parma known in his youth, but also prophetic forebodings of later painting: Delacroix, Nolde, Rouault, even Bacon.

Exactly beneath the dome, a plaque declares that this is Goya’s final resting place—at least so we believe.

There lie the bones of the tremendous painter, creator of so much wonder.

But not the complete skeleton—the skull is missing!

For the most terrifying of Goya’s caprices was the one that, posthumously, starred his own head

Curious, indeed, that rarely in the history of art has there been a man so attuned to the witchlike and the demonic as Goya.

He was struck by a grave illness, the nature of which was never clarified—perhaps a severe form of hemiplegia—that caused him to lose his hearing almost completely.

Deaf and solitary—a solitude that breeds darkness, that breeds monsters. Like the sleep of reason that breeds monsters.

Famous are his sarcastic and burlesque Caprichos and other etchings he called Proverbs and Follies.

An imagination without rest, which reached its darkest point in the decoration of his country house near the Manzanares—the Black Paintings of the Quinta del Sordo, “black” for the shadowy dominance of malignant and perverse creatures, forces that would ultimately turn against the very head that had created them.

He died in 1828, during the night between April 15 and 16, in Bordeaux.

Buried in the Chartreuse Cemetery, he remained in oblivion until 1878, when the Spanish consul in Bordeaux—newly widowed—buried his wife in the same cemetery and saw the painter’s grave in a state of ruin and neglect. He took an interest in the matter.

Years later, he finally succeeded in convincing the state to intervene—the painter deserved better, a tomb in his homeland, perhaps in the Sacramental Cemetery of San Isidro.

So the tomb was opened and…

Upon opening it, we found in a zinc coffin the painter’s bones—“except for the head, which was completely missing.”

“Since the coffin did not appear ever to have been opened, we were led to believe that Goya had been buried already decapitated—perhaps by a doctor, or by some mad lover of rarities.”

The transfer of the remains dragged on, not least because the Spanish government refused to pay for the operation, which amounted to the paltry sum of 1,400 francs.

Only on May 11, 1900, did the bones finally arrive in Spain and were laid to rest at San Isidro.

It was then decided, most fittingly, to move them once again to the place where they still lie—though without the head—beneath the dome of the Florida.

That was November 29, 1919.

And the head?

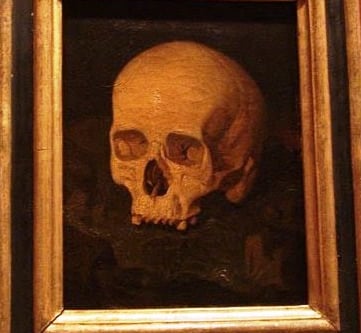

In 1928, the centenary of his death was celebrated, and on April 17, Don Hilario Gimeno announced, to the astonishment of those present, that he had found in an antique shop in Zaragoza an oil painting depicting the lost skull:

“Cráneo de Goya, pintado por Fierros, 1849.”

How and why he came to possess it remains a mystery.

It is believed that the skull of the genius underwent a horrific yet marvelous adventure—fitting for a genius. But let us proceed in order.

One night—perhaps rainy, certainly dark—three men ventured into the cemetery to carry out an unusual theft: to steal the skull of the genius.

And why? For adventure, for art, and for… science.

Or rather, for pseudoscience: a theory known as phrenology, which claimed to diagnose virtues, vices, inclinations, and qualities through the observation and measurement of the skull, divided for that purpose into imaginary compartments.

Zone 26—the seat of intellectual faculty for perspective and color.

Zone 18—home of “wonderfulness.”

Zone 19—imagination.

Zone 20—the spirit of satire.

Qualities that Goya possessed in abundance; what better skull to determine the perfect dimensions of such cerebral regions?

Nonsense, of course—but it is certain that in the period when the glorious painter’s corpse was decapitated, people believed in such things blindly.

Thus, it was a decapitation for science!

A doctor—a phrenologist—studied it, but his companion in the adventure, a painter, kept the relic, perhaps by a law of nature—an object of ultimate inspiration.

Dionisio Fierros kept it among his dearest possessions (though, it must be said, it did not help his inspiration much, as proven by the poor and utterly uninspired quality of his forgotten paintings).

So, where is the skull now?

And here we reach the most painful part: the skull is destroyed.

It was the painter-grave-robber’s own son who, unknowingly, committed the deed.

A medical student, after his father’s death, he found the object without knowing its origin.

It could have been the skull of a simple peasant—and for a medical student, to have a skull all to himself was quite a luxury. Nothing wrong with that—if only he hadn’t had the brilliant (ah, youth!) idea of experimenting at home with his colleagues on the “power of germination.”

They filled the skull with damp chickpeas and waited 24 hours to see the effect.

The effect was indeed that of “the power of germination,” a rather banal natural process.

The chickpeas swelled and… the worst happened. The skull exploded.

Experiment successful. The bones were shared among those present.

“Goya’s skull is not lost, but transubstantiated into all our brains, as in a sorcerer’s mortar,”

wrote Ramón Gómez de la Serna on the matter, in his pompous yet effective style.

A fitting end for such an imaginary, dark, brilliant, and terrible head.

He was, after all, and solely he, in art, the greatest tamer of witches, harlots, and corpse-raisers.

A biography turned into a necrology; a skull stolen for an imaginary science darker than his darkest paintings; a skull destroyed for a childish game.

As in life he scattered colors and lines ablaze with shadowed passion, so in death he scattered the “minutiae of his mighty bones.”

In the end, writes Gaya Nuño,

“Few of us can claim that three fanatics, alone at night in a romantic cemetery, might steal our head.”

In Italiano su Isidora

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Contacts

Or WhatsApp me: