Ten Lesser-Known Masterpieces to Seek Out in Rome’s Churches

Everyone knows that Rome’s churches are essentially a vast museum, a constellation of rooms brimming with absolute masterpieces—works that, moreover, still stand in the very places for which they were created and conceived. Every visitor to Rome has gone hunting for the most celebrated works by the great masters: “So where are the Caravaggios?”, “And Raphael?”, “And Bernini?”, “And Michelangelo?”. No mystery there: they’re easy to find by now; you don’t even need the Touring Club’s red guide anymore. Just ask the web—or follow an art influencer or two. I propose something slightly different: ten extraordinary paintings, works of absolute value that deserve attention and contemplation. Ten pillars in the history of painting, fully visible in Rome’s churches yet overshadowed—socially and symbolically—by more iconic blockbusters. In no particular order.

11/19/202511 min read

1 - Daniele da Volterra at Trinità de' Monti

2 - Giulio Romano at Santa Maria dell'Anima

3 - Taddeo Zuccari at San Marcello al Corso

3 — For those strolling Via del Corso, here’s the perfect art break: the church of San Marcello al Corso. Famous in Rome for its Nativity scene and for the Miraculous Crucifix, which remains one of the most iconic images of this century’s beginning. Pope Francis brought it to St. Peter’s Square and prayed before it, invoking protection and the end of the Covid pandemic. The pandemic ended—for the vaccine, you’ll say. Still, the vaccine arrived quickly… I’ll leave it there.

In any case, the church also features notable frescoes by Perin del Vaga and Daniele da Volterra (yes, the one from no. 1 above the Spanish Steps). But I choose a work that drives me crazy: if I’m nearby, I must enter and look at it—irresistible.

Taddeo Zuccari’s Conversion of Paul (on the road to Damascus), oil on slate (!!), circa 1560–62, in the Frangipane Chapel.

A firework of lights and colors, many figures twisting and fleeing, with Saul falling from his horse as Christ calls him—blinding him and preparing him for his mission. The horse is terrified, small, and beautiful. Jesus sends his divine bolt from a moving cloud; the angels quietly rub their hands: this struck-down man will be the doctor gentium, the Apostle Paul, who will die a martyr in Rome.

Two side notes:

Taddeo was the good Zuccari brother—more talented than Federico, who became more famous.

Another extremely famous Conversion of Paul is in Rome, the one by Caravaggio in Santa Maria del Popolo. Clearly Zuccari’s version came first; Caravaggio saw it, and in my opinion… borrowed a thing or two.

4 - Federico Barocci at the Chiesa Nuova

But let’s rewind: Barocci, like many students arriving from the provinces, had a problem. Rome overwhelmed him—too many people, too much competition, too fast-paced. He was slow by nature. So he invented the story that someone had tried to poison him; few believed him, but he believed himself—and fled back to Urbino under the protection of Francesco Maria II della Rovere. Finally, peace. Barocci continued working for Rome, though: he became one of the key painters of the Roman Counter-Reformation, but from afar, atop his solitary hill. “You want one of my works? No problem—I’ll ship it from Urbino. But I warn you: I am very slow.”

The chosen work can move one to tears; Philip Neri prayed before it, often weeping: The Visitation (1583–86).

Mary visits her elderly cousin Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist. Barocci’s style is unmistakable: glowing, vaporous color, layered and luminous, stirring emotion and tenderness.

In the same church you’ll find another Marian work of his, The Presentation in the Temple, which Philip Neri never saw—Barocci was too slow finishing it.

While you’re there: the three altarpieces of the main altar are by Rubens—too obvious, so I didn’t choose them. The dome and vault are by Pietro da Cortona. And in the first chapel on the right there’s an extraordinary Crucified Christ by Scipione Pulzone. Fun game: try to find the arm of John the Evangelist.

5 - Sebastiano del Piombo at San Pietro in Montorio

5 — Sebastiano Luciani, Venetian, came to Rome seeking fortune, convinced by wealthy banker Agostino Chigi. The “Venetian at the papal court” gamble worked beautifully, and he quickly became Roman in spirit, forging an alliance with Michelangelo aimed at rivaling Raphael.

The plan worked fairly well. Pope Clement VII awarded him the prestigious post of Piombatore Apostolico, keeper of the papal lead seal—basically like joining the board of a major state-owned company today: little work, lots of money. Hence his historical name: Sebastiano del Piombo.

The work is a rare example of oil on wall (not a fresco): The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1518), in San Pietro in Montorio above Trastevere, near Bramante’s Tempietto.

This is a prime example of his collaboration with Michelangelo: the preparatory cartoon seems to have been drawn by Michelangelo himself (quite plausible, as Christ looks like a marble athlete in full Michelangelesque vigor). The image became widely influential and was reused often. In short: Florentine design by Michelangelo, Venetian execution by Sebastiano, in a Roman church under Spanish patronage. Sixteenth-century Italy in one painting. And from outside the church you get one of the most beautiful views of Rome.

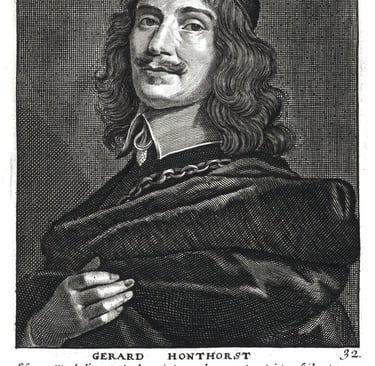

6 - Gherrit van Honthorst at Santa Maria della Scala

6 — Down in Trastevere, less than a five-minute walk away, lies Santa Maria della Scala, next to the famous Scala Pharmacy, the oldest in Rome. Enter, and immediately to the right in the De Battista Chapel is a canvas painted between 1610 and 1618: the Beheading of the Baptist by Dutch painter Gerard (or Gerrit) van Honthorst—known in Italy as Gherardo delle Notti for his mastery of night scenes and chiaroscuro.

Gherardo of Utrecht was a perfect trend-watcher: he instantly grasped what would become the next big thing. He was in Rome during Caravaggio’s meteoric rise; he saw the revolutionary style and thought, “dat werkt erg goed”—“this stuff works brilliantly”—and began painting in Caravaggio’s manner: Caravaggism. Being Dutch, he realized he could make serious money with it. In 1620 he returned home, imported the new style, and founded a tremendously successful academy—very expensive: 100 florins just to enroll. Long story short: he made real money, and his Naturalism became central to the Dutch Golden Age, eventually reaching Rembrandt.

The painting in Santa Maria della Scala is thus the foundation stone of a new artistic chapter.

7- Guido Reni at San Lorenzo in Lucina

7 — Remaining in the seventeenth century but returning to “upper-crust Rome”: San Lorenzo in Lucina, ancient and rich in art.

The non-selection I want to mention: The Temptation of St. Francis by Simon Vouet, a French Caravaggist. Spoiler: the temptation is a beautiful woman…

The work I choose instead is by a great Italian master: Guido Reni of Bologna. A classic still missing from our list: The Crucifixion (1638). One of the most perfect and most copied in history—powerful and hypnotic—placed on the main altar and framed by elegant black fluted columns. Christ appears to exhale his final breath, yet not a drop of blood is shown; his torso is taut, stretched to its limit. Beneath the cross lies Adam’s skull, and beyond, Jerusalem shrouded in a sky darkened by betrayal. A true icon.

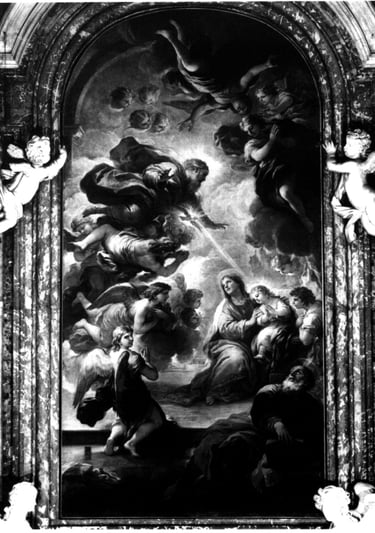

8 - Luca Giordano at Santa Maria in Campitelli

8 — Just outside the Jewish Ghetto stands the majestic Santa Maria in Campitelli, with one of Rome’s most beautiful façades, designed by the rock-solid Carlo Rainaldi. The church was rebuilt to celebrate the end of a terrible plague in Naples in 1656, in fulfillment of a vow made to an icon of the Virgin, still kept inside.

The selected painting is by a wandering Neapolitan who became one of the most important artists of his time, eventually knighted by the King of Spain, Charles II, and serving as his leading court painter for a decade: Luca Giordano—nicknamed “Luca fa presto” for his breathtaking speed (a perfect foil to slow-paced Barocci).

The work, from 1685, is titled The Destiny of the Virgin Mary (or Mary with Her Parents Joachim and Anne), an unusual iconography. The child Mary, in her mother’s arms, is “discovered” by the Father, who—transported by a host of angels—irradiates the scene with golden light and chooses Mary by sending the dove toward her: a sort of pre-Annunciation, a proto-Incarnation. Below, poor Joachim is terrified—and I understand him.

This is the Baroque at full throttle: extravagant, theatrical, slightly kitsch—just as the madrileños like it.

9- Guido Reni at Santa Maria della Concezione

This oil on linen is located in Santa Maria della Concezione on Via Vittorio Veneto, right above the famous crypt filled with thousands of bones (which belongs to this church).

The work is St. Michael the Archangel Defeating Satan. Take a look: you’ve seen it thousands of times. It’s the emblem of the Italian State Police, whose protector is St. Michael—who defeats wrongdoers. Fitting, no?

He is beautiful and blond, long-haired, with a perfect physique—like Brad Pitt in Troy, but purer. With one foot he crushes Satan; with his sword he threatens him; with chains he arrests him; flames barely touch him. He even recalls Obi-Wan defeating Anakin in Revenge of the Sith. The perfect hero, endlessly imitated. And once you’re there, treat yourself to a stroll down Via Veneto.

9 — I’m about to do something I shouldn’t: for piece number nine, I not only go back to 1635, but I also choose a second work by Guido Reni. But it’s not my fault. Before creating the most iconic Crucifixion model of his time, he invented another equally immortal model. A true master of sacred design, our good Guido.

10- Marco Benefial at the Ara Coeli

10 — For the final work we climb into one of Rome’s most important churches—124 steps upward: the Ara Coeli on the Capitoline Hill.

I choose an eighteenth-century work by an artist who was a minor obsession of mine during my studies: another Roman of Romans, Marco Benefial—one of the most underrated painters ever. Well, perhaps I exaggerate—but still, seriously good.

In the Boccapaduli Chapel are two canvases narrating the life of St. Margaret of Cortona. They were presented in 1732 as works by a certain Filippo Evangelisti. But Evangelisti was just a front: the true author was Benefial. He was disliked by the academy, poorly tolerated, considered dangerous—essentially mobbed because he painted differently.

A 1715 decree even prohibited non-academics like him from receiving public commissions. Benefial appealed to the pope and won, overturning the law. But the victory of the “rebels,” of whom he was leader, changed little. Ten years later he still used a front name for his Ara Coeli masterpiece.

Two canvases, as I said: The Death of the Saint and The Finding of the Lover’s Body. I choose the latter.

The saint, elegant and composed, weeps at the sight of the lifeless body of her beloved Arsenio, anatomically flawless and reclining in three-quarter view. In the church his nude body is discreetly covered with a bundle of sticks, but the preparatory sketch at Palazzo Barberini reveals him fully nude—tragically perfect, brutally incisive. Even eighteenth-century Rome, often dismissed as dull, produced beauty.

2 — From a pupil of Michelangelo to a pupil of Raphael—indeed, the pupil of Raphael: Giulio Pippi, known as Giulio Romano, because he was truly “Roman from Rome” (and few great Roman artists actually work in Rome). Giulio’s stellar career blossoms outside the city, notably in Mantua at the Gonzaga court, where he paints applause-worthy giants in Palazzo Te.

But first, as a young man, he trained in Raphael’s workshop in Rome. Then the master suddenly dies on April 6, 1520. “And now what do we do with all these commissions?” The demand for Raphael’s work was infinite: dozens of projects in progress, drawings, sketches, contracts signed and paid for. “Well,” Giulio and the others think, “let’s do them ourselves—we’re good enough; he taught us well, didn’t he?” And indeed, they were excellent—the very best.

So Giulio paints this exquisite altarpiece known as the Fugger Altarpiece (1521), destined for the Fugger bankers, among the five wealthiest families in Europe. They were Germans from Augsburg; fittingly, the painting is in Rome’s German national church, Santa Maria dell’Anima, of which they were major patrons.

The work was meant for their family chapel, but it was so superior that it was placed on the main altar. It is the perfect example of an “exportable” Holy Family with saints for foreign patrons: saints, putti, Madonna and Child, and in the background Roman ruins, an apse flooded by Rome’s dawn light—a real location, at Trajan’s Markets. Saints and souvenirs: Italy hasn’t changed much, has it?

1 — The church of Trinità dei Monti—or more precisely, the Santissima Trinità dei Monti—right above the notorious Spanish Steps, houses several pivotal works of mid-sixteenth-century art: the Late Renaissance, what historians call Mannerism.

My pick for you is Daniele da Volterra’s Deposition of Christ from the Cross, painted in 1545 and located in the Bonfili Chapel.

Daniele da Volterra is remembered as “Il Braghettone,” the man who painted underwear onto Christ in the Sistine Chapel, covering Michelangelo’s nudes. But if he was chosen to retouch Michelangelo—the Divine—there must be a reason. No one painted “in the manner of Michelangelo” better than Daniele. He had an innate ability to balance space, voids and solids, geometry and eccentricity. This painting contains all of that—and it is magnificent.

10 — For the final work we climb into one of Rome’s most important churches—124 steps upward: the Ara Coeli on the Capitoline Hill.

I choose an eighteenth-century work by an artist who was a minor obsession of mine during my studies: another Roman of Romans, Marco Benefial—one of the most underrated painters ever. Well, perhaps I exaggerate—but still, seriously good.

In the Boccapaduli Chapel are two canvases narrating the life of St. Margaret of Cortona. They were presented in 1732 as works by a certain Filippo Evangelisti. But Evangelisti was just a front: the true author was Benefial. He was disliked by the academy, poorly tolerated, considered dangerous—essentially mobbed because he painted differently.

A 1715 decree even prohibited non-academics like him from receiving public commissions. Benefial appealed to the pope and won, overturning the law. But the victory of the “rebels,” of whom he was leader, changed little. Ten years later he still used a front name for his Ara Coeli masterpiece.

Two canvases, as I said: The Death of the Saint and The Finding of the Lover’s Body. I choose the latter.

The saint, elegant and composed, weeps at the sight of the lifeless body of her beloved Arsenio, anatomically flawless and reclining in three-quarter view. In the church his nude body is discreetly covered with a bundle of sticks, but the preparatory sketch at Palazzo Barberini reveals him fully nude—tragically perfect, brutally incisive. Even eighteenth-century Rome, often dismissed as dull, produced beauty.

4 — Staying with Mannerism—the Gen Z of the sixteenth century, following the generation of Masters: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael.

Raphael was from Urbino, and our Federico Barocci was born there too. Barocci came to Rome, had a meteoric rise, and became the favorite painter of St. Philip Neri, the apostle of Rome, Pippo il Buono. The painting I’ve chosen is in his church: Santa Maria in Vallicella, also known as the Chiesa Nuova.

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Contacts

Or WhatsApp me: